Arrest and Exile

In 1845, Shevchenko graduated from the Academy of Art and returned to Ukraine where he began to work for the Kyiv Archeographic Commission and in this capacity visited many towns and villages of his homeland.

In the spring of 1846, in Kyiv, Shevchenko met the young historian Mykola Kostomarov who was an ardent admirer of his poetry.

Together with a group of young Ukrainian liberals, Kostomarov organised the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, a secret political society named after the legendary disseminators of Christianity and literacy among the Slavs. The society called for the abolition of serfdom, broad access to public education, and the creation of a federation of free and equal Slavic people. However, its members imagined they could achieve their aims through sermonising and dissemination of knowledge, ruling out any idea of revolutionary action.

Shevchenko, who headed the more radical wing of the society, attended meetings where he read his impassioned poems which called for an uprising.

In March of 1847, the Brotherhood was denounced to the authorities and its members – Kostomarov, Shevchenko, Hulak and others – were arrested.

For his revolutionary poems which were circulated in manuscript copies, Shevchenko was sentenced to exile as a private in the Orenburg Field Battalion.

Approving the verdict, Tsar Nicholas I added with his own hand: "Under strictest surveillance, with the prohibition to write and paint."

The poet later wrote of the tsar's sentence: "If I had been a monster, a vampire, even then a more horrible torture could not have been devised for me."

In eight days, Shevchenko was delivered to his place of exile. From Orenburg he was sent further yet, to the Orsk Fortress.

The appearance of Orsk was anything but attractive. A solitary hillock rose from a dismal plain. On one side there were the poor huts of the local populace; on the other side were the barracks of the convicts. The only vegetation consisted of prickly weeds and withered sedge.

After the magnificent nature of Ukraine, the green banks of the Dnipro River, the spacious southern steppes and the picturesque avenues of beautiful Kyiv, Shevchenko viewed the wilderness with profound sadness.

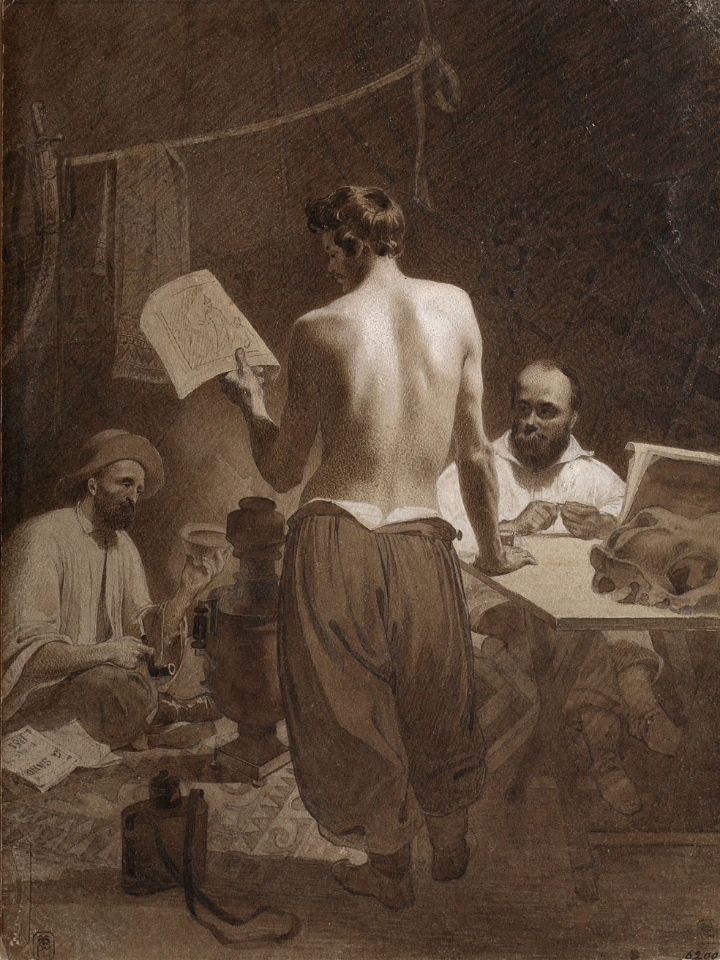

Here began the hard and monotonous life of Private Taras Shevchenko. In the daytime he went through the drills. In the evenings, sitting with the other soldiers in his stuffy barracks, Shevchenko listened to their unhappy tales about beatings and humiliations.

He spent ten years in exile in the distant reaches of the tsarist empire. The degrading treatment he suffered at the hands of his cruel superiors, and the harsh discipline of army life undermined his health. But these punishing circumstances could not subdue his spirit - on the contrary, his hatred of the tsarist regime grew still more implacable. Nothing could break his ardent will to struggle and engage in creative work. "I am tormented, I suffer, but I do not repent," Shevchenko said at the time of his most arduous ordeals. Disobeying the tsar's prohibition and ignoring all threats to his safety, Shevchenko secretly continued to write poetry. It should be noted that among his immediate superiors there were not only cruel martinets, but also some very sensitive and humane people.

During his ten years of exile he composed many powerful works, reflecting the cherished aspirations of all oppressed people. Writing, painting and hoping to gain his freedom were the sole consolations of Shevchenko, Private No.191.

Early in 1848, Taras was offered the opportunity to join a scientific expedition to explore the Aral Sea, undertaken by a group of officers of the General Staff. He gladly agreed as this would have given him an escape from the tyranny of his sergeant-majors and from the stench of the barracks.

Among the many sketches and watercolours he made during the trip, were the ones of the forbidding landscape of the Aral Sea and its shores. These pictures came to serve as important artistic documents.

On Kos-Aral Island, Shevchenko wrote prolifically. In his diary he termed the poetry written in exile a "Prisoner's Muse". It contained both lyrical pieces and the poems Maryna, The Sotnik, and The Sexton's Daughter. His lyrics of this period serve as a poetic record of his life in an "unlocked prison". Other verses of the Kos-Aral cycle are of an intimate nature and are imbued with mournfulness. However, there is no feeling of hopelessness in Shevchenko's poetry of that period. Through the misty curtain of his reality, the poet discerned the bright outlines of a happy Ukraine-to-come without lord and slaves.

Never did freedom seem so precious to Shevchenko as it did there, in exile and bondage. With all his heart he yearned for Ukraine, although she, too, was deprived of freedom.

In winter 1848-49, Shevchenko composed many songs in the folk-song tradition – sad songs and merry ones, serious songs and jesting ones. During the same period, he wrote several autobiographical poems, which carried him back to his childhood and the years of his youth.

In the autumn of 1849, the expedition returned to Orenburg. Shevchenko's sketches and paintings of the Aral Sea were dispatched to headquarters with a petition to have the exile's lot alleviated. In Orenburg he roomed in private quarters and was not subject to the rules of soldiering. He wrote and painted and wore civilian clothes. And then, a young lieutenant informed on him to the authorities. A search was made of the poet's quarters and his books and letters were confiscated.

Soon after, orders were received from St. Petersburg to make conditions worse for Private Shevchenko. Tsar Nicolas I, himself, was behind that command. The poet was sent to the far-off Novopetrovsk Fortress on the north-eastern shore of the Caspian Sea. For the second time he was sternly forbidden to write or paint. He was now watched more closely.

But the poet would not give up. Risking the wrath of his superiors, he continued to write. In his new place of exile, he wrote several stories in Russian, the plots of which unfolded against the backdrop of serfdom.

Shortly before gaining his long-awaited freedom, Shevchenko began to keep a diary which he wrote in Russian. He began it "out of boredom", as he put it, simply because he had " a terrible desire to write" and because he wanted to practice writing. "Just as his instrument is imperative for the virtuoso and his brush to the painter, so must a man of letters practice writing."

He had no idea that his Journal would become one of his most remarkable works. It is more than a biographical document. It is also a unique self-portrait of the man whom Nekrasov called "a most remarkable person of the Russian land” – a self-portrait that allows us intimate knowledge of the poet, his feelings, thoughts and political convictions.

In his Journal, Shevchenko appears as a staunch fighter, incapable of compromise and firm in his belief in the final victory of the people over their enslavers.

We have been accustomed to imagining Shevchenko as he is shown in his most popular portraits. He is depicted with a stern, aged face with a long, full moustache. But this man was, in fact, a person of gentle and sensitive spirit, of lofty and versatile thought, an advanced man of his time.

When Shevchenko was finally released in 1857, during the reign of Tsar Alexander II, he seemed to have been born anew, as though he had sloughed off the hard years of exile. "It seems to me that I'm the same as I was ten years ago. Not a single trait of my inner being has changed. Is that good? It is good!" he wrote in his Journal.